“…Take these pinions, fly behind me: I’ll go ahead, you

Follow my lead. That way

You’ll be safe.

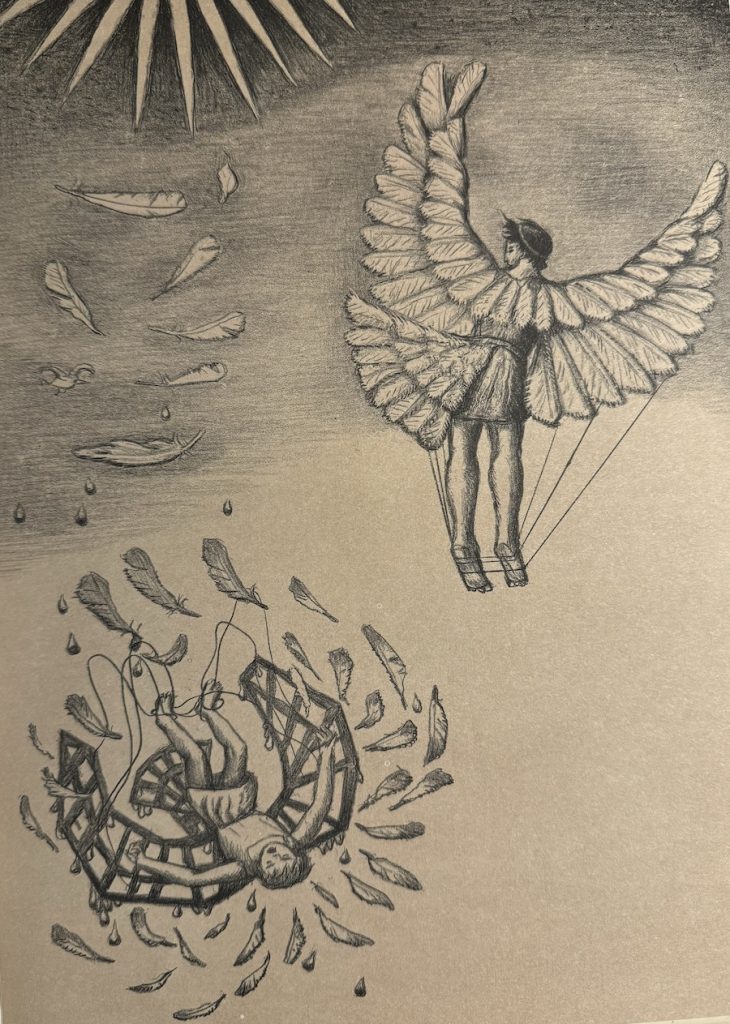

…While he talked, he was fitting

The boy’s gear, showing him how to move

Like a mother bird with her fledglings. Then he fixed his own harness

To his shoulders, nervously poised himself for this strange

New journey; paused on the brink of take-off, and embraced his

Son, couldn’t fight back his tears.

They’d found a hilltop – above the plain, but no mountain –

And from this they took off

On their hapless flight. Daedalus flexed his wings, glanced back at

His son’s, held a steady course. The new

Element bred delight. Fear forgotten, Icarus flew more

Boldly, with daring skill.

Then the boy, made over-reckless by youthful daring, abandoned

His father, soared aloft,

Too close to the sun: the wax melted, the ligatures

Flew apart, his flailing arms had no hold

On the thin air. From the dizzy heaven, he gazed down seaward

In terror. Fright made the scene go black

Before his eyes. No wax, wings gone, a thrash of naked

Arms, a shuddering plunge

Down through the void, a scream – “Father, Father, I’m falling –”

Cut off as he hit the waves.

His unhappy father, a father no longer, cried “Icarus!

Icarus, where are you? In what part of the sky

Do you fly now?” – then saw wings littering the water.

Earth holds his bones; the Icarian Sea his name.

From Ovid, The Art of Love: Book 2, translated by Peter Green

Anyone judging by our popular culture would have trouble distinguishing between an American father and any of the many residents of a clown car, unless maybe that father happens to be a murderous ogre.

On one hand, we have Dad jokes and Dad bods.

On the other, the Latin root-word “Pater” is largely familiar to us for lending the much-despised “Patriarchy” its first syllable.

Viewed through that lens, fathers are either a bit ridiculous, or more than a bit menacing.

But then…

I came across this passage in my reading this morning. The ancient Roman poet Ovid tells the story of Daedalus and Icarus, oddly enough in an erotic poem attempting to illustrate how a male lover might attempt to pin down the wings of Eros, god of love. It’s an odd placement, in one way. Or is it a cautionary tale? A man who ensnares a woman, as Ovid proposes here, risks becoming a father.

If he becomes a father, he risks ever so much more.

Daedalus, it now occurs to me, is quite the figure of a father. At first glance, perhaps, foolish, even ridiculous. Who makes wings out of bird feathers and wax, and proposes to fly with them? Who gives them to a boy, and expects him to follow instructions while using them?

But Daedalus was desperate. He and Icarus lived as slaves under King Minos, who used the father’s genius to his own ends. Daedalus had betrayed Minos, resulting in the death of the King’s beastly son, the Minotaur. Perhaps Minos would not kill his genius slave, but would Daedalus’s son be safe? It seems like a no-brainer that the best revenge for the death of one son would be the death of another.

Daedalus had to get his son away from the isle of Crete. Since Minos controlled shipping and a giant bronze robot guarded the shores, the only way out was up. If he wanted his son to grow to manhood, Daedalus had to give him wings, risk him flying too close to the sun, let him soar. Driven, desperate, ingenious, loving. And this classical example of a concerned father fell prey to every father’s nightmare. The boy flew too close to the blazing chariot of Helios, the Sun, his wings melted, he plunged to his death.

Like Daedalus then, fathers now want to protect their children at all costs. We don’t want them to come to violence. We don’t want them to suffer disease, addiction or poverty. We don’t want them to fly too close to the sun.

And yet we must give them wings. And we must fly on and let them take to the sky.

Oh, we look back a lot. And we cry out a lot, demanding to know where they are. And the nightmare flies beside us all the way, right to the end. We lose sleep, and hair, but probably not weight. We’re ready at any moment to swerve, to fly back, to build any ridiculous device we have to in order for them to escape.

But we let them soar. We have to.