Pardon my adding a preface to an already long piece, but I need to let the handful of people who have been faithfully supporting this blog know that, for now, this is my last update.

Not to be a downer, but… I’m exhausted. Overall. In life. A few months shy of my 60th birthday, I’m looking back on decades of frantic activity, or a consistent drive to always be accomplishing things, and I’m asking, “What the hell was THAT?”

In the word of Basil Fawlty: “That was your life, mate.” “That was quick. Do I get another?” “Sorry”

I’ve overloaded myself with things to do, and, again not to be a downer, they haven’t amounted to much in the long run. And now I’m very, very tired. I realize that it’s time to not have so many deadlines hanging over my head. And the ones I can eliminate are the self-imposed ones, like writing every day even when I don’t feel up to it, and publishing a blog entry every week, even when I don’t have a topic.

Funny thing is, I DO still have topics. And I may write about them. But for now I’ve got to stop feeling like the earth will not spin if I don’t write. I hope that’s okay. I appreciate all of you who have taken time out of your own busy days to read my words. That seems to be a thing that’s fallen out of fashion, reading. I’m glad you took the time to be unfashionable with me.

Anyway, here’s Narcissus. And I’ll be back in this space, well… when I’m back

“Who am I?” It’s a good question, isn’t it? A lot of us, perhaps unconsciously, rephrase that question to “What am I?” The answers?

I am a father/mother/son/daughter

I am a husband/wife/partner

I am a Caucasian/African/Asian/Latin

I am a Christian/Jew/Muslim/Pagan/atheist

I am a heterosexual/bisexual/gay person/transgender person/queer person

I am a Republican/Democrat/libertarian/socialist

But you’re not any of those things, not in total–partially because none of those are things. They are concepts, symbols that mean different things to different people. They are qualities, labels or abstractions of things that can be observed about us. But I, as a human being, am not identical to the concept of “a Christian.” There is no such thing as “a Christian.” There are billions of individuals, past and present, who belonged to Christian churches or professed Christian beliefs. Each one of them is different to all the rest.

And, here’s the thing: most of those abstractions are not self-assigned. They’re bestowed upon us by others, and they come pre-loaded with expectations. We each allow our sense of our self to be determined largely by others, and then, having accepted that we are what they say we are, we struggle to live up to their expectations of that thing. Or to disprove their incorrect impressions of that thing. Which is not really a thing, just an abstraction.

That abstraction becomes our identity because we have allowed ourselves and others to commit the error of identity, that is, equating a single concept (“Christian”) with a very complex entity that is a human being. Saying “John is a Christian” is, in one sense, saying, “John is exactly a Christian and nothing but a Christian, and John has only those attributes which are denoted by the label ‘Christian.'” It’s imprecise. It’s limiting. According to the father of General Semantics, it’s even a recipe for madness.

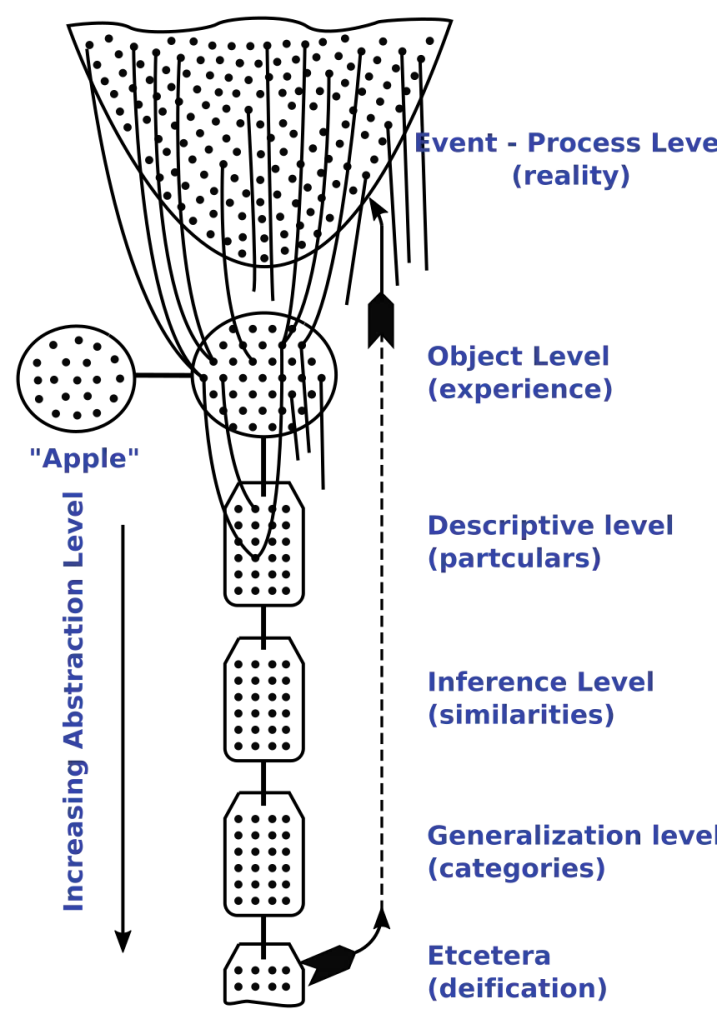

Briefly (lest I lull you to sleep forever), Alfred Korzybski, author of Science and Sanity, developed a model for explaining how any object, including another person, is perceived by our minds. He called it the Structural Differential, and it consisted of a parabola, which represented the infinite nature of an event in time and space, joined by strings to a disk, which represented the object that event is perceived by the human mind to be, joined by more strings to a series of labels, like luggage tags. All of these shapes are depicted as being full of holes. Those holes represent characteristics. Some holes are connected by strings to the next level down. Some are empty. The empty holes represent characteristics that are not perceived at the lower level of abstraction. The human mind begins processing all of this at the bottom. So, if the lowest label is, “A Christian,” it will not have a string connecting it to the hole in the disc which tell us the object in the real world has a measurable I.Q. of 184. And the disc, the highest level our senses can perceive, is missing characteristics that lie within that parabola that goes on forever. In the case of an event that is represented in the “real world” as a human being, that means there are things about that human being that are just unknowable. And there are a lot of things that, seeing that single, dangling tag that says, “A Christian,” we have not bothered to find out.

TLDR? Words that describe us are not–cannot be–equal to all that we are in time and space. Because we know ourselves from the inside, at a level above the five senses of others, we are closer to understanding that parabola than they are. We are best-equipped to build the sense of self that we need.

We do need the help of others to do this. They can give us more data about ourselves. Look at the structural differential model. Those strings represent your senses, your nervous system, gathering data. Others can also gather data, and that’s more data about yourself that you can use. You can’t see yourself only from the inside.

But I’m going to place a caveat on Robert Burns, who said,

“O, wad some Power the giftie gie us

To see oursels as others see us!”

(If only some power would give us the gift of seeing ourselves as others do.)

They might also really confuse us or start us down a dangerous rabbit hole, if others are persuasive. Burns’s giftie might only be a gift in the sense that a stuffed crocodile lamp is a gift. It’s a burden that we feel we must accept and be grateful for, but our lives would be a lot less cluttered if we could throw the damn thing in the dumpster.

It can be dangerous to see yourself from the outside, though. Consider Narcissus, whose story I re-told last week.

Suffice to say, Narcissus got in trouble, as predicted by Tiresias, because he saw himself and saw his own beauty. Was he embittered by love, because a boy had committed suicide out of love for him? Or was it not just that? I think Narcissus was probably very jaded by his encounters with humanity at large.

I suspect Narcissus was like a lottery winner: Everybody wanted something from him. They wanted to feel that they were good enough to be loved by the most beautiful boy on Earth. It must have been exhausting, emotionally and physically.

So let’s think about this. We’re all traumatized by broken love. Check. Go back before that. Narcissus’s mother wanted to protect him, as all parents do. Perhaps she tried too hard. She hovered. Like Phaethon coming too close to the earth with the chariot of the sun, she may have burned her child by keeping maternal warmth too close.

Affection can be catching. If a child is beloved by one, he likely will be by others. He’ll also be strong, confident, and more attractive. So Narcissus attracted many.

So, the abstractions Narcissus received about himself:

I’m lovable

I need to be protected

I’m popular

I’m sexually desirable

Other things, such as, I’m good at sports, probably figured in.

Conclusions:

I get more attention than anyone, so I’m better than others.

Ameinias killed himself for love of me, so I may be more trouble than I’m worth AND

Love is destructive.

Then he saw himself in the water and fell in love.

By what standard of beauty and desirability did he judge himself irresistible?

What was different about the reflection as opposed to all the lovers he had rejected? The reflection was him, so it knew exactly how he felt. Stephen Fry told a version of this story and said that Narcissus could see that the boy in the water loved him as he loved the boy. Matching desire. But, still, Narcissus’s love became desperate, like all the others. And so the boy’s love became desperate. Before, Narcissus had not returned love. Now, the desperate love became overwhelming.

Was Narcissus a virgin? Probably not. Boys don’t reject sexual encounters, by nature. (Perhaps legislation has changed that erstwhile fact of human nature? If so, let me know. I haven’t kept up.) He probably had fun, at first, being offered all this sex from all these partners.

Why had Narcissus never returned anyone’s love? They probably all became obsessive and overwhelming. Eventually, he would have pushed away anyone who approached him, untried. Also, none of them came to him as an equal. They came as beggars.

When you are perceived as wealthy or talented, everybody wants a piece of you for their own, petty reasons. Narcissus took the out of self-obsession. Maybe he even took the out of suicide.

Narcissus was overwhelmed by the sense of identity foisted on him by others. He was overwhelmed by the expectations of others. That can happen to any of us, even if we are not the most beautiful human ever born. (And how do you know you’re not? Because someone told you so? Now, I want you to think about that.)

Maybe what Narcissus deserved to be remembered for was not a destructive personality disorder, but the all-too-common phenomenon of being overwhelmed by the expectations of others. Which are all just labels placed upon us, nearly always via the error of identity: Narcissus is beautiful and therefore will fulfill all of my expectations of what a beautiful person should be.

What’s the antidote? Use the data provided by others, but don’t be dominated by it. Have your own, impervious sense of self. But be realistic about yourself. You should be in love with yourself, but not obsessed. The tragedy of Narcissus’s self-love is that he loved himself the way others loved him—wanting the superficial, seeing only the abstractions and labels, not perceiving the whole self.

If he had really known the boy in the water, if he had come to the conclusion that the companionship of that boy was all he needed to be whole, Narcissus might have been happy. And then it wouldn’t really have mattered how long he lived, would it?

Up yours, Tiresias.