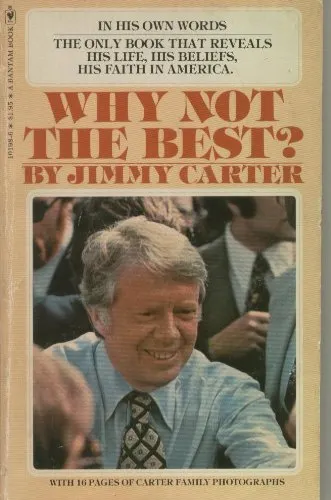

Somewhere in my parents’ house (because nothing ever leaves my parents’ house), there is a copy of a slim paperback titled, Why Not the Best?

Okay, it’s not my parents’ house anymore, it’s mine. My son and his family live in it. And it’s likely that the book in question did leave, because my mother went on a binge of book donating late in life. She got so obsessive about it that she started donating books that belonged to other people. We had to have a talk.

This book was, I believe, a bestseller, and it introduced the world to a man named Jimmy Carter, just-departed Governor of Georgia. Richard Nixon had, only two years earlier, resigned the United States Presidency amidst scandal, and his elected Vice-President, Spiro Agnew, had preceded him in leaving office amidst scandal. So the Presidency fell upon a non-elected Vice President, Gerald Ford. By all accounts (including that of his opponent in the 1976 Presidential election, the aforementioned Jimmy Carter), Ford was a good and competent man, and, observed John Chancellor of NBC news, even a gifted athlete. Unfortunately, Jerry Ford had a habit of tripping and falling on camera. Jerry Ford pardoned a man that a lot of people hated then as much as many now hate the color orange. Saturday Night Live, already gearing itself up to be the sole source of political news for a large segment of the American electorate, had Ford portrayed by Chevy Chase as a dithering, absent-minded bumpkin.

The Presidency was not in good shape. The Democrats had last controlled the White House in the person of Lyndon Baines Johnson, who, despite an ambitious and oft-lauded program of domestic reform–“The Great Society”–lost mass approval for his expansion of the unpopular Viet Nam War. The Democratic Party was in no better shape than was the G.O.P. vis a vis credibility of Presidential candidates.

Along came an outsider, a peanut farmer, a Southern Baptist, a Sunday School teacher, a Southern governor, who not only won the Democratic Party’s nomination (away from the third political scion of the Kennedy dynasty, no less) but triggered something of a cultural phenomenon. Jimmy Carter’s prominent teeth were caricatured far and wide. The antics of his brother Billy served to fill the cultural void left by the mass-cancellation of rural comedies like Green Acres and the Beverly Hillbillies a few years earlier. Indeed, a two-season rural sitcom, Carter Country, earned decent ratings for ABC starting in 1977.

I was eleven years old and had grown up under the ceaseless barrage of news of the Viet Nam War (in which my father served for six weeks on special assignment in Thailand) and the Watergate scandal. Jimmy Carter was a breath of fresh air. A lot of voters, my conservative Southern Baptist parents included, were energized by the change in tone he brought to politics. They read Carter’s book, watched both party conventions, and I began to absorb my first lessons in American politics. Ironically, my father also supported Ronald Reagan in the 1976 G.O.P. primary. I don’t know how he would have voted in November if Carter and Reagan had faced off four years early. I think my mother, a church-going Democrat, would still have voted for Carter. My dad almost never went to church during my life, and he was a staunch Republican. But the contest was Ford v. Carter (That “v,” by the way, is read as “versus,” not “verse.” They are two words with distinctly different meanings.), so my dad voted for Carter.

Carter, of course, won that election. There followed my first four years of being very aware of and engaged with the persona of the U.S. President, and the last four years of my life in which I felt pleased with the person in the Oval Office.

I will admit (because I try to be honest) that some of my admiration for Carter is tribal. I always thought of myself as a displaced Southerner, even though I grew up in the nominally “Southern” state of Maryland. My parents were both from Western North Carolina, and I considered myself a small-town native of Appalachia who just happened to be born in Northern Virginia’s sprawling metropolis and then shipped off to Howard County. I grew up going to Rolling Hills (nee Holiday Hills) Baptist Church, which I joined by baptism in 1974. I was devout in my Christian faith and disgustingly moral. My classmates laughed at me if I ever tried to swear. It was always a rather pathetic effort. I did not hate people who were not like my family and my church brethren. My grandmother had impressed on me that we must try to love everyone. She did, by the way, love everyone.

But Jimmy Carter, two years younger than my father and two years older than my mother, was a man who might have sat next to me in church, might have taught me in Sunday School. Indeed, after his Presidency, he welcomed anyone who might wish to attend his Sunday School classes in Georgia. That suggests an open, accessible leader, and that, for me, is the image he always projected. As excited as many of my Baby Boomer friends were when “one of us” took the White House in the person of Bill Clinton, that’s how excited I was when “one of my own people” took office in 1977.

Alas, public excitement waned and the gentle ribbing turned to condemnation. By 1980, most Americans, aided and abetted by the twin animated crickets-on-their-shoulders that were Hollywood and the sadly emerging phenomenon of news-as-entertainment, had decided that Jimmy Carter was a weak president who was solely responsible for soaring unemployment and inflation, to say nothing of hours-long lines for gasoline and the year-long Iran hostage crisis.

By this time, I was fifteen and still could not vote; but I had strong opinions about the 1980 Presidential election. I watched all the debates, including those leading up to the primaries. I decided that George H.W. Bush was untrustworthy, Lyndon Larouche was alternately funny and scary, and John Anderson seemed like a reasonable guy. Indeed, when Anderson declared himself as an independent candidate, I, like Mike Doonesbury, was all for him. If 15-year-olds could have voted, Anderson would have had my vote.

Looking back 44 years, I think I was being impractical in my choice, and that my adult self would have stuck with Carter.

I went to college in 1984, a committed liberal. Meeting all kinds of different people and being exposed to new ideas tested that conviction. I voted for Walter Mondale in 1984 specifically because he had been Jimmy Carter’s Vice President, and, despite John Anderson, my respect for Carter the man had never diminished. By 1988, I was married, working and owned a home. I voted Republican. I regretted it, but I did. George H.W. Bush was a disappointment. 15-year-old me’s instincts, it turns out, were spot-on.

Throughout the 1990s and 2000s, unhappy with the direction my Country had taken politically, I clung to the ideas of Jimmy Carter. I bought and read his books, I listened to samples of his Sunday School classes. How I wish I’d made the trip to actually be there! Jimmy Carter became and remained my hero. He walked the walk of my childhood faith, loving others, giving of himself, forgiving others, and being brutally honest about himself, even if it meant admitting he felt lust in his heart.

Carter earned a reputation as “America’s Best Ex-President,” notably for his continued involvement in the Arab/Israeli peace process, for which he won a Nobel Prize in 2002, and for his work with Habitat for Humanity, literally building homes for people who lacked them. Now it is gratifying to see even his legacy as President being re-examined, with a fellow Nobel-winner, economist Vernon Smith, granting him the title, “The Great Deregulator,” and Cato Institute Vice President Gene Healy acknowledges Carter as “Our last peace President.”

Reading Healy’s words, I re-experienced my long-lost resentment toward the 1980s, a decade I saw as bellicose, obsessed with image and ass-kicking, and devoted to the new for the new’s sake. Throughout high school and college, I wonder what had happened to the America I grew up in, where we laughed at Archie Bunker, lauded Hawkeye Pierce, celebrated our history, and recognized violence as the last refuge of the incompetent. It makes me very nostalgic for a time when, whatever else was wrong, at least I didn’t cringe when the President opened his mouth.

At 59, I do not accept the labels “liberal,” “conservative,” or even “libertarian.” I have ideas that are liberal, I have ideas that are conservative. Political alignment tests usually identify me as libertarian. I am a member of a Methodist Church, but I have ideas that derive from Hinduism, Buddhism, Quakerism and a host of other traditions. I am me. My ideas do not define me. I define them. President Jimmy Carter helped me learn to do that.