-

Steve Englehart’s work is special to me. I discovered him (indirectly) at the tender age of nine at the school book fair. I went to a small private school with about a dozen other kids in my fourth grade class. You’d think our book fairs would have been less spectacular than the ones in public school, but they were a hundred times more magical. Perhaps it was the library, a parlor in an Eighteenth Century mansion and one of my favorite places on earth when I was little. (I visited recently and saw that it had been gutted and turned into another classroom. How traumatic to see your childhood refuge come to such a fate!) Perhaps it was the lack of hovering adults, which my public school book fairs had possessed in abundance, telling me the books I wanted were too old for me, too focused on the sciences, too whatever. Whatever it was, the small, private school book fair was an event to me, and it was there, in 1974, that I found a Marvel Comics calendar featuring pictures of most of their now-iconic characters. I had just started reading comic books, and I knew none of these colorful personages save Spider-Man, who after all had his own cartoon still running on weekday mornings. I was fascinated by a picture of some people called The Avengers, which featured a towering figure in green with a red face, and a woman in scarlet who fascinated me and does to this day. I ordered the calendar and, on my next trip to the grocery store, bought an issue of this Avengers comic. I learned the impressive man was the Vision and the exotic lady the Scarlet Witch. He was an android; she was a mutant. Both were rejected by “normal” humans. They were in love. As the stories progressed, Wanda the Scarlet Witch delved more and more into “true” magic, as opposed to using her mutant probability powers. They became a symbol of the interdependence between technology and spirituality. I devoured their adventures as they got married had children and learned their secret origins. Then later creative teams dissected him, wiped their children out of existence and turned her into a genocidal maniac; because we all know that androids can’t have feelings and women can never be trusted with power. At least that’s the attitude of writers who know how to expertly press the emotional buttons of forty-something fan boys. I would assert that those same cynical writers are subscribers to the common belief that one must choose “teams” in the “contest” between science and faith, and thus the idea of a witch and an android being in love just ran against their philosophical grain. Or perhaps I’m giving them too much credit for deep thought.

I was fascinated by a picture of some people called The Avengers, which featured a towering figure in green with a red face, and a woman in scarlet who fascinated me and does to this day. I ordered the calendar and, on my next trip to the grocery store, bought an issue of this Avengers comic. I learned the impressive man was the Vision and the exotic lady the Scarlet Witch. He was an android; she was a mutant. Both were rejected by “normal” humans. They were in love. As the stories progressed, Wanda the Scarlet Witch delved more and more into “true” magic, as opposed to using her mutant probability powers. They became a symbol of the interdependence between technology and spirituality. I devoured their adventures as they got married had children and learned their secret origins. Then later creative teams dissected him, wiped their children out of existence and turned her into a genocidal maniac; because we all know that androids can’t have feelings and women can never be trusted with power. At least that’s the attitude of writers who know how to expertly press the emotional buttons of forty-something fan boys. I would assert that those same cynical writers are subscribers to the common belief that one must choose “teams” in the “contest” between science and faith, and thus the idea of a witch and an android being in love just ran against their philosophical grain. Or perhaps I’m giving them too much credit for deep thought.The writer who developed these two characters so brilliantly for a dozen-plus years until their demise was Steve Englehart. At the same time, he wrote a version of Captain America which set the tone for the type of comics storytelling that was going to revolutionize the industry in the 1980s. He went on to turn the Justice League of America into a group of real people instead of “TVs Super-Friends,” and to write the definitive version of Batman. When those characters were developed for TV and movies, it was largely Englehart’s work which advised the screen writers. Indeed, he wrote the first treatments for Tim Burton’s Batman, and the film The Dark Knight was heavily based on his Dark Detective mini-series. (If you hated The Dark Knight, don’t hold it against Englehart. Personally, I considered it a well-made movie that was too intense to watch twice. Englehart’s work is never so jarring and manipulative of the audience.)

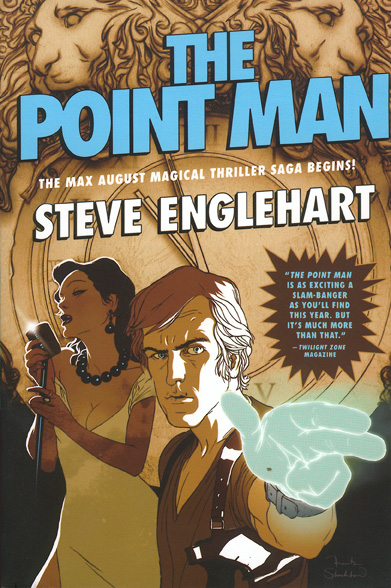

Englehart rarely writes comics any more. The industry seems to have little use for “the old guys.” Ironic that the old guys may outlive the industry itself, as badly as it seems to be failing of late. But the comic readers’ loss has been a gain for those who read prose. In 1980, having left New York and the comics business for a while, Englehart tried his hand at a novel, The Point Man. It featured a Viet Nam vet turned DJ named Max August. Max met, through rock star Valerie Drake, a centuries-old alchemist named Cornelius Agrippa. Agrippa took Max as his pupil and introduced him to the vast, invisible, supernartural world which affects our reality daily, though most of us aren’t aware of it. Max became a warrior for good on this invisible plain, and, along the way, became immortal. The novel went into print and fairly quickly back out. These were not the days when comic writers graduated to being millionaire hollywood screenwriters before they turned thirty, so book-buyers didn’t know the name above the title. (Ironic, since Englehart was the first of their breed to have his work almost directly translated to the screen.)

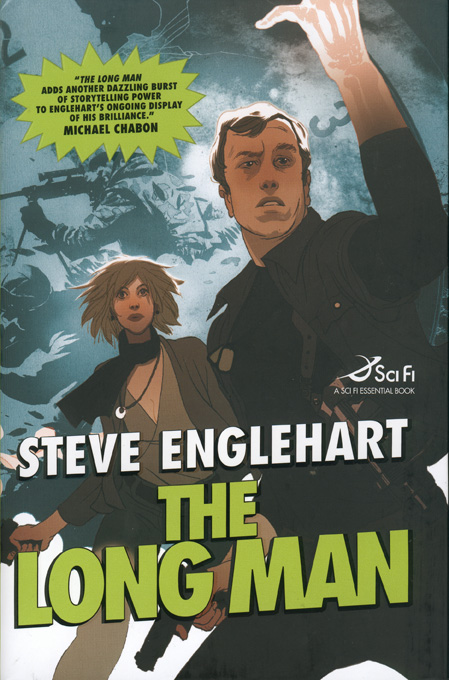

Decades later, however, Englehart got The Point Man back onto bookshelves, gently re-written, he says, to bring out Max’s immortal aspect, and this time with a sequel beside it. The Long Man picks up the action in the present day, with Max still 35 years old physically, now a widower and no longer a student, his teacher having been killed in the late 80s.

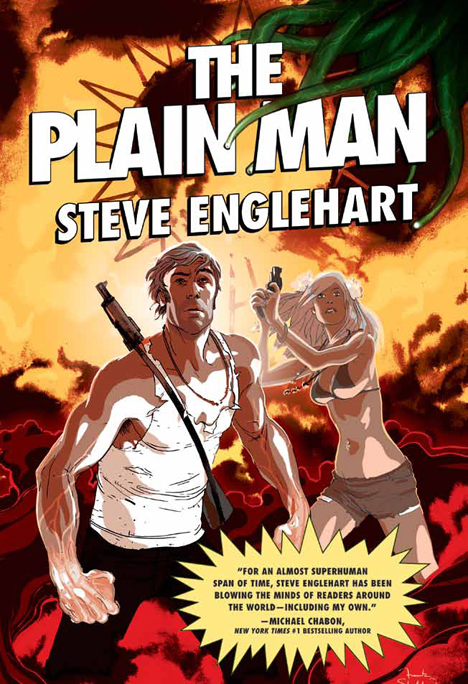

The third entry in the series, The Plain Man, has Englehart hitting his stride with Max August. Max and his new disciple / lover Pam, a former research scientist, attend an annual Pagan festival called Wickr. They’re on a mission, tracking agents of the secret conspiracy known as the FRC and its inner circle, the Necklace. Part of the fun of this latest volume is that Englehart builds a team around Max. In addition to Pam, a mere mortal trying to come to terms with a world she only just learned existed, he’s aided by Sly, AKA Coyote the Trickster, and his also immortal lover Scorpio Rose. These two are characters Englehart created for Image comics many years ago, but they translate very well to prose. Englehart is at his best handling team dynamics, playing characters fears and insecurities against each other, letting them be sounding boards for each others’ personal growth. And his characters always grow, never mind the fact that three of these four don’t age.

The plot moves quickly, with a suspenseful race against nuclear armageddon (at least for Nevada) at the climax. The villains are despicable, especially the pair of hired guns we follow throughout the story. They’re so evil you want them dead and you want it to hurt badly. My only minor complaint is that we do spend a lot of time in the company of the villains, and the the leaders of the conspiracy are complex, developed charaters. We see their motivations and their inner turmoil, but not enough to make them sympathetic at all; so it wasn’t pleasant to see inside their heads. I found myself wanting to get back to the heroes. This is a personal quirk of mine, though. I never like too many scenes in the villains’ camp without the hero. I prefer a story to stick to the heroic POV. That may be because, so often, I feel that the villains’ camp scenes are just padding the story for length. I can’t say that here, though. Here it’s an author who is really good at characterization making his villains, well, characters. I guess I’d just say I wanted more time with the protagonists, because I never can spend enough time with Englehart’s heroes. (Although I must say that Aleksandra, the immortal “Big Bad” of the story, managed to hold my interest despite having no redeeming social value.)

The secret conspiracy plot is classic Englehart. His Captain America run involved a Secret Empire, bypassing American democracy and running the Country to its own whims. It had hooks into the Oval Office, and it was suggested that Nixon himself was its leader. The FRC, likewise, has a strong hold on government. It put operatives in place during the Bush administration, and continues to weild power under Obama. With a story like this, it would be easy to alienate at least half the audience. Such a tale could easily come off as a sermon against right wing politics, or at least against the Tea Party. And there is a brief, one-paragraph rant about the Tea Party by one of the villains. Englehart maintains a careful balance, however. I am fairly sensitive to political messages in media, and, being neither Republican nor Democrat, am irked when writers grind their political axes and throw too many sparks. I was not offended by the politics of The Plain Man, though I think they give the reader a pretty clear idea of the author’s politics.

Easily my favorite part of the book, though, is a conversation Max and Pam have about Pi. An irrational number, Max points out, Pi is impossible to complete quantify; and yet our technological advancement is absolutely dependent upon it. Pi is impossible, but essential. The passage lasts only about two pages, but it’s a succinct and eloquent explanation of the place of the sacred in a rational world.

The series will continue with The Arena Man. I would recommend reading the books in order. For his Avengers, Batman and Captain America work, may I recommend:

Avengers: Celestial Madonna

Avengers: Coming of the Beast

Avengers: The Serpent Crown

Vision and the Scarlet Witch: A Year in the Life

Batman: Strange Apparitions

Batman: Dark Detective

Captain America: Secret Empire

Captain America: Nomad I’m always surrounded by collectibles, but my son Ethan gave me this beautiful vinyl sculpture of my particular favorite, the Scarlet Witch. She sits on my Grandmother’s table by my favorite reading chair.

I’m always surrounded by collectibles, but my son Ethan gave me this beautiful vinyl sculpture of my particular favorite, the Scarlet Witch. She sits on my Grandmother’s table by my favorite reading chair.

REVIEW – Steve Englehart’s Max August in The Plain Man

(Visited 133 times, 1 visits today)