Saturday, this was the thought of the day for me. I awoke to learn that a young man I knew, not a close friend but someone I liked very much, was dying. Indeed, he was dead before I finished my first cup of coffee. I’d known he was sick. I’d known he was in the hospital. I’d just thought, “This is a young, healthy guy, and he’s coming home.”

He didn’t come home. I was… angry. How stupid is that? It’s no one’s fault. Someone catches a rare infection. I assume doctors do everything they can, but, we’re not immortal. What’s the point of getting angry?

Well, maybe it was pointless, but I was angry. Young fathers, young husbands, shouldn’t die. That should be in the rules.

It’s not in the rules.

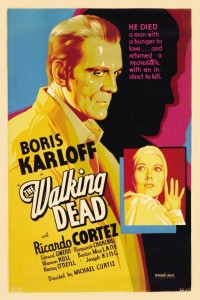

So I moved on with the day: housecleaning, eBook editing, a convention meeting. Saturday night I’d promised a friend I’d finally, after years of missing it, attend film historian Greg Mank’s annual Hallowe’en talk at the Imaginative Cinema Society. Greg has written several books and done several DVD commentaries on the classic horror films of the likes of Karloff and Lugosi. After Greg’s fascinating talk about 1934’s The Black Cat, we watched another Karloff film, 1936’s The Walking Dead. No, it’s not related in any way to the popular series on AMC.

So I moved on with the day: housecleaning, eBook editing, a convention meeting. Saturday night I’d promised a friend I’d finally, after years of missing it, attend film historian Greg Mank’s annual Hallowe’en talk at the Imaginative Cinema Society. Greg has written several books and done several DVD commentaries on the classic horror films of the likes of Karloff and Lugosi. After Greg’s fascinating talk about 1934’s The Black Cat, we watched another Karloff film, 1936’s The Walking Dead. No, it’s not related in any way to the popular series on AMC.

It’s the story of a man whose death should make you angry. Someone is very much to blame for it, and it’s very unfair. Boris Karloff plays a down-on-his-luck musician who’s framed for murder and executed for the crime. Then he’s brought back to life by three guilt-ridden scientists who could have prevented his execution, but didn’t move quickly enough. When he comes back, the executed man knows things he didn’t know before. He knows how he was framed. He knows who did it. How does he know these things? Well, obviously that knowledge came to him on “the other side.”

The lead scientist (Oscar-Winner Edmund Gwenn, famed as Kris Kringle in Miracle on 34th Street) spends the rest of the film trying to find out what happened to Karloff’s character while he was “away.” He wants an answer to one very simple question:

“What is death?”

He doesn’t get an answer. He learns only that the Lord our God is a jealous God, and He guards His secrets well. Man is not meant to know what death is.

Fair enough. But seeing a film that posed the question, on that day of all days, very much put it foremost in my mind.

What is death?

You know how, when you Google a word, you get an immediate definition? I don’t know who sponsors that, but one comes up if you Google, “What is death?” It says:

“The action or fact of dying or being killed; the end of the life of a person or organism.”

Okay. That tells me it’s the end of life, something that’s also not defined. I don’t know much more than I did before.

What is death?

A Buddhist website, death-and-dying.org, has a more open definition:

“Death is the cessation of the connection between our mind and our body.”

That’s actually in keeping, apparently, with the definition given in the very first edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica. I like that a little better. It doesn’t presume to know whether death is the end. It just says it’s an end. But it doesn’t say what comes after, now does it?

What is death?

Many people believe it is the end. Nothing comes after. An article on the Atheist Foundation of Australia‘s website has this to say about the subject:

“Atheists maintain that the concept of humankind having a unique supernatural ‘soul’ is simply a primitive notion which has no basis in fact and that religious organisations are guilty of perpetrating a colossal fraud on ignorant and gullible people, chiefly through the indoctrination of infants. They are aided and abetted by the media who fear adverse reaction affecting profits if the facts are revealed.”

I don’t really think “facts” enter into it, since no one’s died and come back to say there’s nothing after death. That’s because, um, if there IS nothing after death, there’s no way to… oh hell, you get it, right? It’s a neat little trick, arguing a point that, if the point itself is valid, cannot be proven.

But I respect people who can live life without believing there’s anything after. I don’t know how they stay sane, but I respect their belief. I just don’t believe that. The good thing about that is, if I’m wrong, by the time I know for sure, I um, won’t be able to know.

What is death?

Death can be the starting point for fanciful stories, probably because we need to challenge our fear of it.

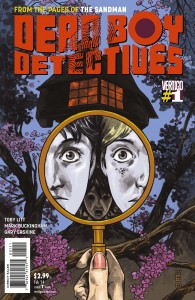

One of my favorite comics, Dead Boy Detectives, is about Charles and Edwin, a pair of ghosts who both died (about eighty years apart) on the grounds of the same awful British boarding school. It’s been playing in its latest story arc with the idea of being “half-alive, half-dead:” a living person’s heart stops, but their brain still lives, a ghost confronts its corpse. The living have near-death experiences, the dead have, I guess, near-life experiences.

One of my favorite comics, Dead Boy Detectives, is about Charles and Edwin, a pair of ghosts who both died (about eighty years apart) on the grounds of the same awful British boarding school. It’s been playing in its latest story arc with the idea of being “half-alive, half-dead:” a living person’s heart stops, but their brain still lives, a ghost confronts its corpse. The living have near-death experiences, the dead have, I guess, near-life experiences.

(And in DBD’s parent series, The Sandman, Death is an actual character, a very attractive young girl.)

A lot of religions teach that death is part of a punishment / reward system. Great warriors go to Valhalla. Great heroes go to the Elysian fields. Evil people go to Hell. Fundamentalists believe that there’s no scope for evil. If you’ve ever done one evil thing, and you don’t ask to have it purged from your soul, you go to Hell.

A lot of religions teach that death is part of a punishment / reward system. Great warriors go to Valhalla. Great heroes go to the Elysian fields. Evil people go to Hell. Fundamentalists believe that there’s no scope for evil. If you’ve ever done one evil thing, and you don’t ask to have it purged from your soul, you go to Hell.

I don’t believe any of that. I can see why a lot of people want to, though. Rewards for them if they’re good, punishment for their enemies who’ve been bad. Of course, the person holding the belief is never bad, in their own eyes.

Personally, I’d like to believe that, at the instant of my death, a continua craft will appear before me. Lazarus Long and his family will leap out, grab me, perform whatever medical interventions are necessary to keep me alive, then take me to their home on a distant planet and restore my body to the way it looked when I was twenty.

Who knows? Maybe the future is fiction. Maybe I’ll get my wish. I really want to meet Lazarus’s redheaded twin sisters, and I really want to be young and strong when I do.

But that’s not reality. That’s fantasy. It comforts me, that’s all. And, after I’m gone, if it comforts you to believe I made it to Tellus Tertius and am dwelling amongst my fictional heroes, I hope you can believe it too. Whatever my loved ones do, when I’m gone, I hope they’ll be happier that I lived than they are sorry that I died. In short, I hope they’ll be happy.

Because, if you’re not happy, death is a tragedy. Or maybe it’s a merciful end to a tragedy.

What is death?

It’s what comes next. And we don’t know what that is. Sorry, guys. There’s no Excel spreadsheet with the deliverables and the milestones and the estimated completion dates. There’s no budget. There’s no contract. There’s no scope of work. Whatever comes next, you can’t plan it. You can’t invest for it. You can’t study, as you can for a test.

But maybe death is a test. Maybe what comes next is nothing but a way for you to prove how good you are, tossed into a situation where you don’t have any resources but your wits and your integrity… your soul. The best part of you.

Scary? Yup.

But I guess it makes me a little less angry, to believe that something so wonderful as a human being can be hurt, frustrated, tested… but not destroyed.

I don’t think my musings amount to much. Sometimes my writing is just my way of harnessing my own thoughts and feelings. Probably, at such times, it’s not of much interest to others. There’s a much better overview of death, its science, and beliefs about it here.