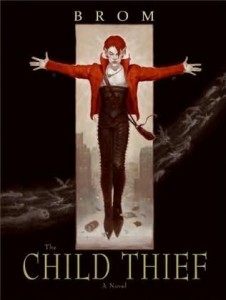

I said in my brief Goodreads entry on this book that it is “beautiful and disturbing,” and I think that’s the best tagline I can give it.

I said in my brief Goodreads entry on this book that it is “beautiful and disturbing,” and I think that’s the best tagline I can give it.

Fantasy artist Brom has created a dark version of Peter Pan, or, perhaps more accurately, he has re-imagined Peter Pan, highlighting some pieces which are vaguely referenced in J.M. Barrie’s original: the fact that there’s a lot of killing in Neverland, that Peter is a barbarian, a savage, and that there’s a strong possibility that when his Lost Boys become too old, Peter kills them or has them killed. All of this Brom details in his afterward. He also describes how he returned to Barrie’s original source material (or at least material that influenced him strongly), that being the legends and folktales of the British Isles.

Hence, in this story, Neverland is the Isle of Avalon, which was taken magically from proximity to England sometime after King Arthur’s time, so that the magical inhabitants could live in relative peace, far away from humanity (“menkind”) and our civilization. I say “relatively,” for the inhabitants are not actually very nice to each other even without humanity being present, and at least some of them are known to have traveled to the human world where they’ve both interbred with humans and preyed upon them. Indeed, Peter, a halfbreed fairy child born in Medieval times and cast out to die in the woods by his dreadful human family, is lured to Avalon by the daughter of the witch Ginny Greenteeth, who wants to drink the blood of a little human boy, and, it seems, has done so often in the past.

Avalon is historically populated by Fairies, Pixies, Trolls and Elves. When Peter first arrives there, it is a paradise, largely ruled by Modron, The Lady of Avalon, though regions also belong to her sister Ginny, and the forests are apparently ruled by their brother, the horned one. The paradise is lost, however, when humans arrive, several shiploads of them. Avalon’s escape from civilization has been only temporary after all. It’s been relocated to what will someday be named New York Harbor, and, while at the time of its arrival the New World was populated only by non-Europeans who lived in harmony with nature, understood the significance of a magical land, and had no interest in invading it, things quickly change. “Civilized” Europeans come to America, claiming it as their own, and they quickly try to do the same to Avalon. They defile the beaches with their crosses, and begin hunting and killing the magical creature of the woods, including the trees which are living and bleed when cut.

Avalon as an analogy for the New World, and the magical creatures as an analogy for the Native Americans is a bit heavy-handed. I personally find the “noble savage” concept a bit cliche, and even offensive. I get that there’s a disconnect between magic, religion and science, but the whole “people who worship nature gods and don’t use their higher intellectual skills are inherently more moral than the rest of us” rant gets old, both here and everywhere else it’s used. To be fair, later in the book, Brom gives us a glimpse inside the heads of the European invaders as well, and we do get to see another side of the argument. It comes late, though, and the tone has long been set. It didn’t stop me from enjoying the book, but it made me roll my eyes, only because it is an overused idea.

The invading humans become “Flesh Eaters,” grisly creatures whose flesh has blackened as though their skin has burned to a crisp, and whose red blood has run black. Slowly but surely, they’re burning the forests of Avalon. Again, an analogy for the way civilization is supposed to be fouling the earth, I suppose. These Flesh Eaters are the pirates to Avalon’s Neverland, as the Lady is somewhat analogous to both Tinkerbell and Neverland’s mermaids. And, of course, Avalon has its Lost Boys. They’re called Devils, though, in honor of the fact that Peter is considered a devil child. They’re not all boys, either, and they didn’t just happen to get lost. They were spirited away by Peter because he wanted other kids to play with. He did get their formal consent to carry them away, and they all left horrible lives to come with him, but he certainly wasn’t open and honest about the amount of danger they were heading into, with any of them.

The book is told largely from three points of view. After a brief prologue wherein we meet a young girl named Cricket, a victim of sexual abuse whom Peter rescue and delivers to Avalon, we’re introduced to Nick. Nick is fourteen and the main protagonist of the story. When we meet him, he’s on the run from drug dealers, a fresh wound from a branding iron on his arm, carrying a very valuable cache of drugs that he’s stolen from them. It seems his mother has rented rooms in his grandmother’s Brooklyn home to these louts, Nick has tried to alert the police of their illegal dealings and been tortured for his trouble, and now he’s stolen their drugs to sell so he can get the hell away from New York and live on his own. He’s caught and about to die painfully when Peter arrives. The magical child makes short work of Nick’s would-be assailants. He then invites Nick to come with him to a magical place of safety. Nick thinks the kid is nuts, but he doesn’t have a better option. He follows Peter through an enchanted mist, filled with monstrous creatures and littered with dead bodies, and arrives in Avalon, where he’s inducted as a trainee devil. From Nick’s point of view, Avalon is not paradise (and, to be fair, it isn’t by the 21st Century) nor is it a place of safety. It’s a cult run by feral children who worship Peter like a god.

The second point of view is Peter’s. After he meets Nick, we slowly learn his history through flashbacks. We see that life has been hard for him, and he really is just a lost child in search of a family. He has a fixation on the Lady of Avalon, and desperately wants her for a mother. But he was no better received by her relatives when he tried to live with her than he was by his own human family, and so he lives in Deviltree (literally a large hollow tree) with his kidnapped followers.

Late in the book, we begin to also see events through the eyes of the Captain, one of the Flesh Eaters, captain of the expedition that brought humans to Avalon centuries ago. We are slowly led to see that this is not Captain Hook, this is a good man, a basically decent and moral man, as far a morality goes for most men. He has no desire to hurt other people, but he’s been drenched in the philosophy (don’t snicker–most of us are drenched in it too!) that an enemy is not really a person, and it’s okay to kill him, to take his property, and to destroy his way of life. So, while we see that he despises the hypocrisy of the religions leaders who hold his people in thrall, and we see that he misses his own children, and wants nothing more than to adopt and “save” one of the Devils, we also see that he’s willing to lead expeditions to kill the denizens of Avalon. He just thinks it could be done a bit more mercifully. Still, the reader can easily develop sympathy and admiration for this man, and hope that he gets his wish to find a child and give at least one of the Devils a “normal” life. Ultimately, it seems, the Flesh Eaters have not lost their souls. Just some of them had very twisted ones to begin with.

Nick is the anchor, though. He’s the kid from our own time with whom we closely identify. His skepticism and independence make us comfortable with him. The detours into Peter’s and the Captain’s head give us sympathy for another point of view, but Nick’s vision is pretty much our own. He reacts to the magical world the way most of us would: with fear, suspicion, and critical analysis, coupled with a good helping of wonder. He’s the closest thing there is to a hero in the book. Peter is completely amoral, and the Captain too happy to kill. Nick, while he does reluctantly become a warrior in Peter’s army, maintains a conscience, feeling remorse that he’s left his mother behind and repeatedly asking Peter, how many kids have to die? How many lives will be lost to Peter’s desire to protect Avalon and its Lady.

This is an affecting book. It grabs hold of you with its playfulness and spirit of childish joy, even if it is a bit laced with teen angst and a sense of discontent. You feel sorry for every kid and what he or she is going through, especially Nick and Peter. You get a sense of the senselessness of war, violence, and giving your life away for a cause, because it’s usually someone else’s cause. It made me sad, it made me angry, and it did occasionally make me laugh.

But I warn you: the good guys do not win. The cost Peter pays to save his Lady is too high, and the author does not spare us. We feel that cost along with Peter. But more, the good guys do not win because, ultimately, Peter is not a good guy. He’s a nigh-immortal force of nature. Like Nick, I cannot ultimately forgive Peter. A night spent weeping in the park over the kids who died (which is how he spends his final moments with us in the book) does not make up for all the death he’s brought about. At the same time, it’s hard not to love him. He is the spirit of the wild in us, the spirit of unrestrained joy in living. The scene in the Department store at the beginning of the book, when he takes Nick “shopping” after hours, embodies this brilliantly.

Recommended, but be prepared for some pain.