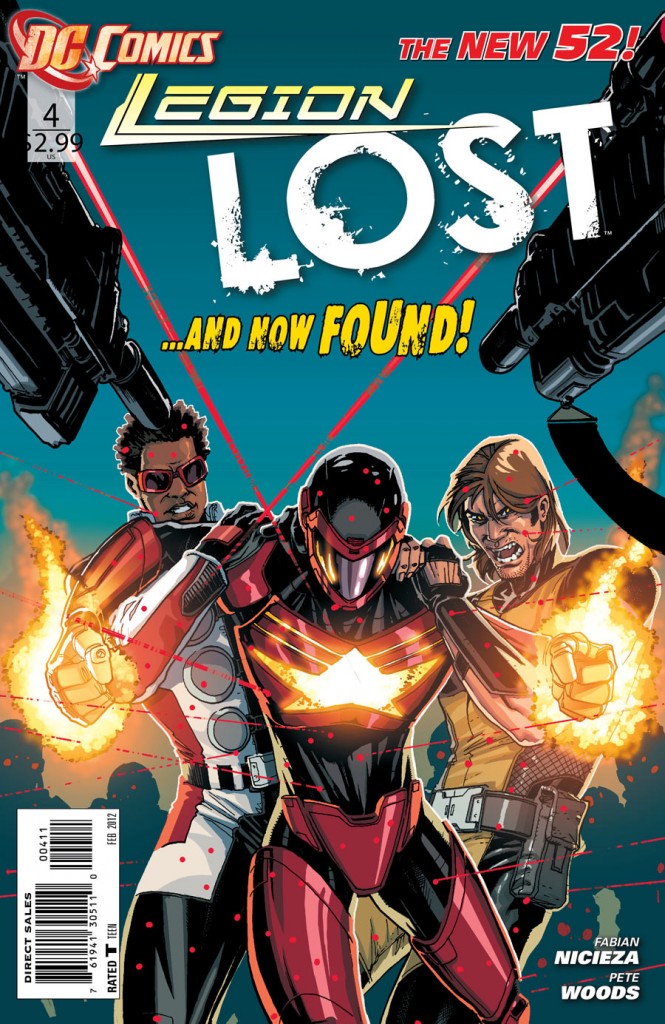

This week I’m not reviewing so much as ranting a bit. Okay, my rant is touched off by something I read, something which I would recommend, something which deserves a good review. The “something” is the latest issue of Legion Lost, a title which is part of DC Comics much-touted “New 52″ experiment. In short, Time Warner told its child company, DC Comics, shepherds of Superman, Batman and the Justice League, that it was losing money and needed to “do something.” The “something” chosen was to take a bunch of iconic characters with already much-rewritten histories going back to the 1930s in some cases, and, well, re-write their histories again. More precisely, DC decided to remove their established histories and start again from ground zero, except, um, where they didn’t. The bottom line is that it’s almost impossible to explain to a casual observer exactly what the “New 52″ is, or what it does to the characters. It does something different to each character and title, all in the hopes of making young people who prefer to watch reality television instead of reading comic books turn to reading comic books. So, what is the “New 52?” Other than a cynical marketing ploy, I got nothing.

I have to say, though, that Legion Lost is an unfortunate title. Why it was picked is a little beyond me. There was a book called Legion Lost about a decade ago, and, while some fans loved it, it was rooted in a period during which all comic art was murky and incomprehensible, except when compared to the murky and incomprehensible plots and dialogue they illustrated. Calling a new Legion title that’s supposed to be fresh and original by this name is a bit like calling your edgy new character-driven SF TV series Plan Nine from Outer Space.

The comic that bears the title, though, is not unfortunate. Written by Fabian Nicieza, it concerns a team of legionaries who come to the 21st Century to prevent a time traveling mass murderer from wiping out the human race. Nicieza is a good writer, and he’s made the story enjoyable thus far. Indeed, it and its companion title, The Legion of Super-Heroes, are two of only three DC Comics I bother to read any more. (The third title is Aquaman, which seems also to have escaped the history-rewriting virus.)

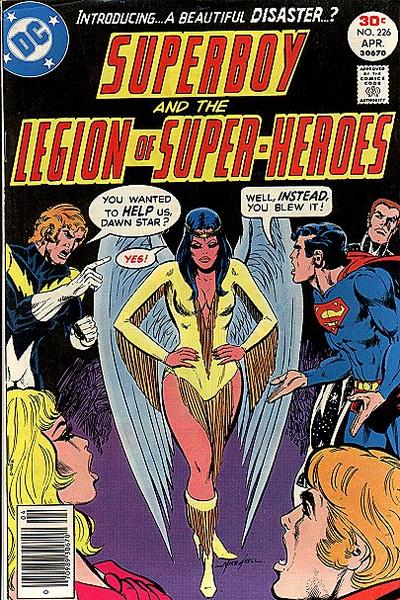

So why did I say I’m going to rant? Well, there’s a line in the narration of the story this month (Issue #4) which just torqued me. I don’t necessarily hold against the writer. It’s very possible he intended it to be a harsh statement, issuing from the unique perspective of the narrator. The narrator is Dawnstar, created in the late 1970s by the aforementioned Mr. Levitz and Mike Grell, one of my all-time favorite illustrators. Dawnstar is an Amerind, descended from Native Americans who colonized the world of Starhaven, and, apparently, preserved their cultural traditions. When she was introduced, having a Native American character in a futuristic comic series was pretty cool. There aren’t too many such characters in mass media even today. But Dawnstar herself always struck me as cold and arrogant. Never more so, though, than when in this issue she describes 21st Century humanity thus: “Their minds are so – unevolved – so limited…” She asks her telepathic comrade, Tellus, “How do you do it? Sort through so much… filth?”

Ouch. Statements like that bug me, coming from anyone carrying the title “hero.” Yes, I’m all for characters having distinct opinions, even negative personality traits. And let’s face it, bigotry is a human foible from which none of us is entirely immune. More, this is a future-based story, and one of the reasons we tell stories about the future is so we can cast a critical eye at our own time, or own place and our own attitudes.

But… dammit… There’s a difference between looking at a culture, any culture, and saying, “They lack knowledge, they’re making mistakes,” and saying that culture is “stupid and backward.” The latter is the attitude of manifest destiny, the idea that anyone who isn’t from our culture is not blessed by God ™ and thus is wrong, evil, even, to their core. Ironic that this attitude, then, is coming from a Native American character, even one from a thousand years hence.

Science fiction which presumes to show us how we might look to people from the future can be useful. Presumably, when we hear the words of criticism coming from a sympathetic protagonist in a story, we take that person’s side to a degree and think, “Yeah, y’know she’s got a point there.” But if the protagonist is unsympathetic and/or her words are too shrill, the criticism can easily be mistake for simple hatred, and it thus doesn’t fulfill its function of making us think. It just makes us angry. (Yes, I’m well aware that making the reader angry can be considered a legitimate goal, but I would submit that that’s true only if you make the reader angry enough to think in some constructive way. Otherwise, you’ve just provoked destructive emotion. Above all, storytelling should be a creative, not a destructive force.)

I flash back to an episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation at the end of its first season. Now this show was all over the map, philosophically. As far as making you think goes, when compared to its predecessor series, it often came off shallow. Never mind the fact that Patrick Stewart could speak more prettily (and more fluidly) than William Shatner; the fact is JL Picard just didn’t have as much to say as did JT Kirk. But the episode which came to my mind as I read this Legion issue was one called “The Neutral Zone.” I recall reading it was written over the course of about four days because they had an open slot in the schedule. The brevity of its development showed and showed badly. The story had a beginning and middle, but no end; and its attitudes toward 20th Century humanity, particularly that segment which lived in the United States, was offensive.

In the story, three humans are found in cryogenic sleep… somewhere. A derelict spaceship, I guess. (It’s been a while, and the episode is not one I would deliberately go back and watch!) After making endless fun of the idea of cryo-sleep to extend life, the crew revive the three. (Intentionally? Again, I don’t recall. Maybe not, since they were so offended by the idea that anyone would want to extend his life that I recall being surprised that they didn’t just phaser the poor bastards out of existence.) The three are a CEO, a housewife and … I guess he was a cowboy or something. (Yeesh, am I gonna have to watch this mess just in the name of accuracy?) Let’s just call them Grumpy, Dopey and Happy. Those were pretty much their character beads. Most of the focus, naturally, was on the CEO, since he wanted to shell out money to have all his demands met. This caused the Next-Generates to shake their heads, smile placidly, and make dismissive remarks about what a stupid, backward culture these people came from. (Watch Steve suppress the temptation to say that it must have been a stupid, backward culture to produce a TV program where an episode like this was not only written but filmed! Oops. Guess that didn’t work.) I seem to recall that Counselor Troi and the Mon Capitan himself were the two lead pooh-poohers of our poor backward selves, and they didn’t skimp on the platitudes about how wonderful it is to live without money and to accept that humans have no control over their own destinies. (They said something like that. As I said, the script was a mess!)

In the midst of all this, the Romulans show up. Why? Well, the script is called “The Neutral Zone.” Apart from that, I guess there was some leftover latex on the makeup bench from the last Klingon episode, so more aliens needed to be re-designed with prosthetic foreheads. As the prophets tell us, everybody wants prosthetic foreheads on their real heads. Troi lectures Picard about who the Romulans are, telling him that “their belief in their own superiority goes beyond arrogance.” Proof positive that humanity in the 24th Century has evolved beyond the use of mirrors, ‘cause otherwise Troi might have, I dunno, looked in one and seen a pot talking to a kettle.

But there’s more to this than the fun of seeing how bad bad writing can be (and that crack is directed only at the Next Gen episode, not at Nicieza’s Legion script.) The mindset that those we don’t understand or with whom we disagree are stupid or, worse, evil is evidenced in so many other places than the pages of comic books or the frames of old TV shows. Nor is it the exclusive province of those who ran the Crusades, those who colonized the American West or the slavers who kidnaped Africans for profit. Nor is it limited to those who look at our ancestors and reflect, not on their wisdom or perseverance, but only on how “ignorant” and “unsophisticated” there were.

No, this mindset becomes more and more apparent to me each passing day as I watch the news (I try not to watch the news, but it hunts me down and pours itself into my eyes and ears) or surf the web, or look at Facebook. A lot of us are being, not only judgmental of our fellow humans, but extremely chauvinistic and hidebound by groupthink. I use “chauvinistic” not in its modern sense, i.e. the attitude of a man who thinks women are inferior, but in keeping with the original definition of chauvinism as given by Wikipedia: “an exaggerated, bellicose patriotism and a belief in national superiority and glory… By extension it has come to include an extreme and unreasoning partisanship on behalf of any group to which one belongs, especially when the partisanship includes malice and hatred towards rival groups.”

This is nowhere more aptly (or more disturbing) demonstrated than in the Tea Party vs. Occupiers conflict. It seems most of those who are opening their mouths (or tapping their keypads) in public have chosen a side; but what strikes me is that they haven’t chosen a side in an argument, they’ve chosen a team. Consider this headline to an article shared with me by a friend on Facebook. (I am blessed – and I mean that sincerely – to have friends on both sides of this issue. That means I get an awful lot of links shared with me to news items and editorials about all kinds of political issues.)

“Democratic Senator Ron Wyden Turns Traitor, Stands With Paul Ryan On Privatizing Medicare.”

Traitor? Really? For those who don’t know, Senator Wyden has been an outspoken supported of Internet rights, taking a firm stance against legislative proposals like SOPA and ProtectIP, which violate the First Amendment, and serve only the interests of Big Content – Hollywood and the Recording Industry – which has lobbying power to put the NRA to shame. I don’t know a lot about Wyden, but I respect what he’s done to prevent a few companies putting a stranglehold on the Internet in the US. His behavior has suggested to me that he must possess both some intelligence and some ethical sense. That doesn’t mean I’d vote for him. It means he and I agree on what I consider to be an important issue, so, if he expresses an opinion on something else, I’ll give him a fair hearing. Maybe I’ll disagree, but I’ll be interested to know what he thinks. Being neither a liberal nor a conservative, I’m accustomed to take an a la carte approach to the opinions of a lot of people.

But the attitude of the commentator here is not so reasonable. “Ron Wyden has turned against liberal ideals in favor of the extreme right wing desire to kill Medicare,” he raves, and “Wyden has long been considered one of the champions of liberalism and he has now turned traitor.” This suggests to me that the writer does not believe Senator Wyden is entitled to think about an issue. He is not entitled to have divergent opinions from “the group” on an issue. Indeed, he’s not supposed to be seeking solutions that work. He’s to adhere to the political orthodoxy and be loyal to his “team.”

I don’t know much about the plan in question here. I just know I’m very uncomfortable when I hear words like “traitor” and “turned against” being used to describe political discourse. We’re not talking about a man who sold arms or secrets to military opponent. We’re talking about one of our own elected officials, who’s proposing a plan to solve an ongoing problem. Whether you like the plan or not (and I have no opinion as yet), “traitor” is not a word that should be used. But I guess the thinking is that Wyden has dropped the “progressive” flag and picked up the “conservative” one. Which, apparently, makes him stupid and backward.

Wouldn’t it be more productive to say, “Gee, I usually agree with that guy. I wonder what led him to take a stand so different from mine?” Is it just easier to call him stupid? Because it makes us feel better? Or just because it spares us the pain of having to think too hard? We should be careful. You never know when there might be a winged super-hero from the far future hovering over us, ready to call us stupid and backward.

I mentioned recently that I’ve been reading comic books since 1974. I mostly preferred super-hero comics, and I’m not entirely sure why, although it’s clear that most readers do. I think, for me it’s because they allow an escape from reality, they generally allow for exciting, colorful imagery, and they have that sense of romantic heroism that is lacking in, say, sword and sorcery stories. I’ll probably explore what I mean by “romantic heroism” in a totally separate article. Suffice to say here that I use it to mean that the characters in the story have a sense of right and wrong, are working toward a just goal, and portray an ideal of people as they should be, not merely as they are. Superman is a person as we’d like to believe people could be. Conan the Barbarian, on the other hand, has little to advertise him as a hero. He can get away with running around in a loin cloth and he wields a mean sword. That’s true of lots of real people, so Conan did nothing for me. (Red Sonja, on the other hand… Pretty girls need no excuse. I’m sexist that way. Sue me.)

I mentioned recently that I’ve been reading comic books since 1974. I mostly preferred super-hero comics, and I’m not entirely sure why, although it’s clear that most readers do. I think, for me it’s because they allow an escape from reality, they generally allow for exciting, colorful imagery, and they have that sense of romantic heroism that is lacking in, say, sword and sorcery stories. I’ll probably explore what I mean by “romantic heroism” in a totally separate article. Suffice to say here that I use it to mean that the characters in the story have a sense of right and wrong, are working toward a just goal, and portray an ideal of people as they should be, not merely as they are. Superman is a person as we’d like to believe people could be. Conan the Barbarian, on the other hand, has little to advertise him as a hero. He can get away with running around in a loin cloth and he wields a mean sword. That’s true of lots of real people, so Conan did nothing for me. (Red Sonja, on the other hand… Pretty girls need no excuse. I’m sexist that way. Sue me.)